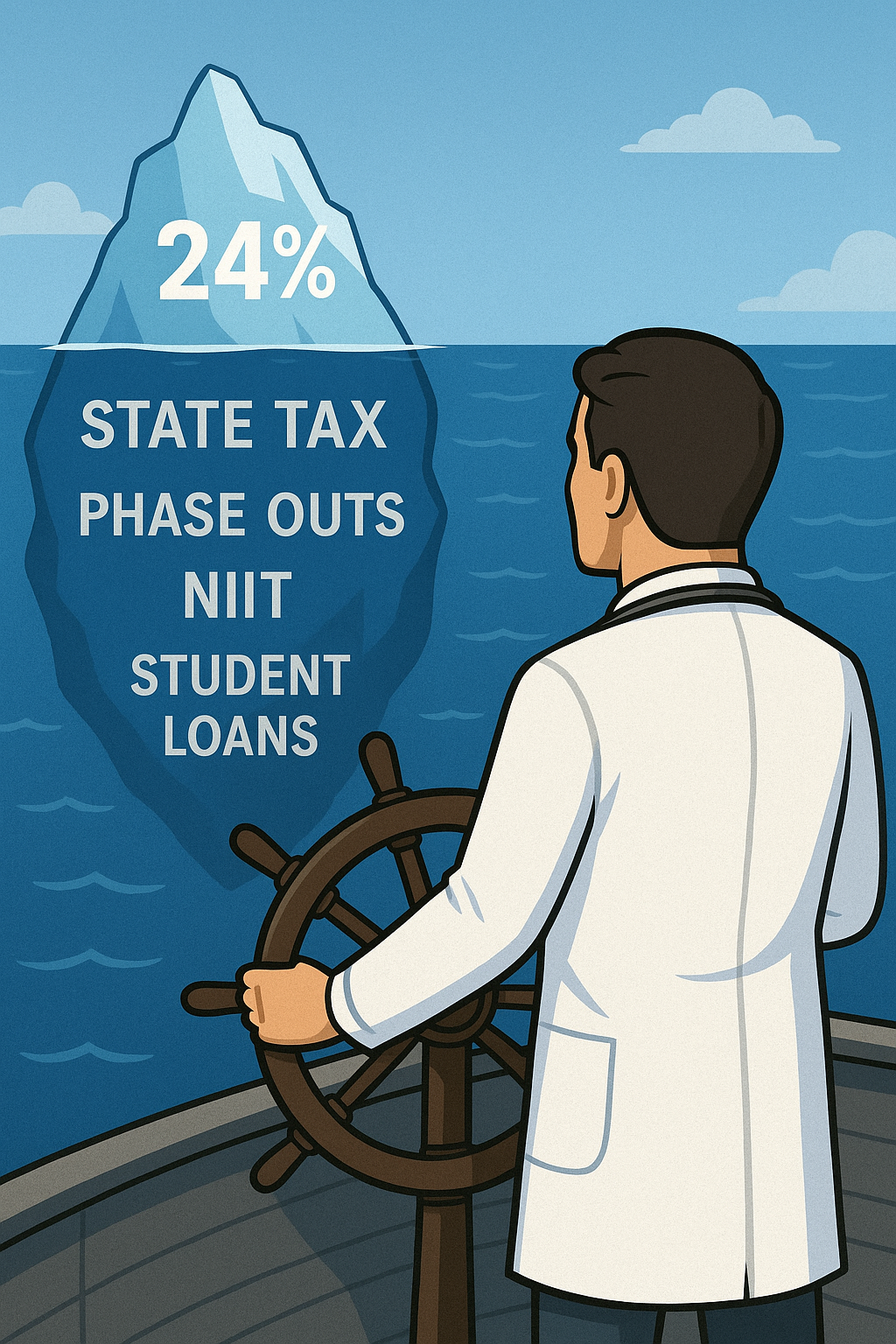

Why Your Marginal Tax Rate Isn’t 24%

Planning ahead can steer you away from a Titanic tax bill.

Most people quote their marginal tax rate from the federal tax brackets. But your true marginal rate is the sum of several layers of taxes—federal, state, payroll, and sometimes even city. And your marginal rate can differ depending on whether the income is earned (salary or self-employment), passive (investments), or from a business.

Let’s look at the major layers.

1. State Income Taxes

If you live in a state with progressive taxation—California, Hawaii, New York, Oregon—your state marginal tax rate can exceed 10%.

Some cities, like New York City, also add their own local income tax.

If you might relocate in the future, timing matters. Deductions are often more valuable while you’re in a high-tax state. Deferring income until after a move to a lower-tax state can generate real long-term savings.

2. Payroll and Self-Employment Taxes

Employees:

Pay 6.2% Social Security tax up to the annual wage base ($184,500 in 2026).

Pay 1.45% Medicare tax on all wages.

That’s a combined 7.65% on earned income below the wage base, dropping to 1.45% afterward.

Self-employed individuals:

Pay both the employee and employer portions (15.3%), though the employer half is deductible, making the effective rate about 14.1% below the wage base, and 2.68% afterward.

On top of that, most high-income earners pay an Additional Medicare Tax of 0.9% once income passes certain thresholds.

And don’t forget state payroll taxes—unemployment insurance, disability insurance, or local payroll assessments—all of which can slightly nudge your true marginal rate higher.

3. The Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)

The NIIT adds a 3.8% surtax on investment income (interest, dividends, capital gains) once your Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) exceeds $200,000 (single) or $250,000 (married).

Example:

Dr. Smith, single, earns $200,000 and has $5,000 of investment income. For the next $5,000 he earns, he’ll pay not just income and Medicare taxes, but also an additional 3.8% NIIT—until his MAGI passes $205,000, when the tax falls away again.

4. Tax Credit Phaseouts

Phaseouts occur when a credit decreases as your income rises. The Child Tax Credit is a classic example.

Each $1,000 of income above the threshold reduces your credit by $50. That means a family can lose $2,200 of credits over just $44,000 of income—effectively a 5% marginal rate increase.

Once you’ve fully lost the credit, the marginal rate drops again. Phaseouts like these can create strange pockets where your true marginal rate temporarily spikes.

5. Tax Deduction Phaseouts

Deductions reduce taxable income rather than tax owed, but phaseouts here can be even more painful.

Consider the enhanced State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA):

Full $40,000 deduction available if MAGI ≤ $500,000.

Reduced to $10,000 if MAGI ≥ $600,000.

That $30,000 deduction disappears over $100,000 of income—an effective 10.5% increase in your true marginal rate (35% × $30,000 ÷ $100,000).

Other deductions like the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction work similarly, phasing out gradually and creating “no-man’s-land” income zones where your next dollar is heavily taxed.

6. Student Loans and “Shadow Taxes”

If you’re on an Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan, your payment (10–15% of discretionary income) scales directly with AGI. Reducing AGI by $10,000 could lower payments by $1,000–$1,500—and increase future forgiveness.

That’s functionally a 10–15% marginal “tax” on income, even though it’s technically a loan payment.

If you eventually pay off loans or if forgiveness is taxable, the long-term effect is smaller—but the short-term marginal impact is real.

7. Retirement Considerations

In retirement, new marginal factors emerge:

Social Security taxation: Up to 85% of benefits can become taxable once your MAGI crosses static thresholds.

Medicare premium tiers (IRMAA): Crossing a threshold can raise premiums sharply, adding another “cliff” effect.

While these aren’t traditional taxes, they behave like them, influencing your true marginal rate later in life.

Case Study: When Marginal Rates Go to the Moon

Dr. Smith, a 1099 contractor in Honolulu, earns $300,000. His spouse earns $240,000. Together, they file jointly with two kids and a combined MAGI of $550,000.

Their approximate marginal tax stack looks like this:

Tax Rate

Federal - 35%

Hawaii - 11%

Medicare (self-employment) - 2.68%

Additional Medicare - 0.9%

SALT Deduction Phaseout- 10.5%

QBI Deduction Phaseout ~14%

Student Loan Payments (IDR) - 10%

Total marginal rate: ~84%

When your combined taxes and phaseouts approach that level, every extra dollar earned is worth barely 16 cents. For someone like Dr. Smith, maximizing deductions and deferring income isn’t just smart—it’s essential.

The TaxSmart Takeaway

Your marginal tax rate is rarely what the IRS bracket says. It’s a constantly shifting blend of federal, state, payroll, phaseouts, and even “soft taxes” like loan repayments and benefit cliffs.

Understanding how these layers interact helps you decide:

When deductions are most valuable

When to accelerate or defer income

When relocation or family changes shift your planning priorities

The U.S. tax code is extraordinarily complex, and no two taxpayers’ situations are the same. The smartest move is to work with a financial planner or tax professional who can help quantify your true marginal rate—and teach you how to make it work in your favor.