The Self-Employed Physicians’ Guide to the OBBBA Part III: Charitable Donations

Donating to charities is still an excellent tax move, but the Big Beautiful Bill might reduce how much of this you can deduct after 2025

Since the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017, charitable donations have been a very fertile ground for making the most of tax planning opportunities. Because the SALT deduction was capped and the standard deduction doubled, this limited the deductibility of donations. One workaround to this was the bunching strategy.

As I discussed in my previous post, more taxpayers will go back to itemizing as a result of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). Taxpayers who find that their SALT deduction, mortgage interest, and other itemized deductions exceed their standard deduction will opt to do this, regardless of how much they contribute to charities. In this situation, they can deduct 100% of their charitable donations in 2025. However, because the SALT deduction phases out above certain levels of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), some taxpayers will find that their SALT deduction remains capped at $10,000 annually, and the bunching strategy will remain important.

In other words, the changes to the SALT deduction by themselves change how we look at charitable donations. What’s more, the OBBBA has introduced a couple of fairly minor changes to how charitable donations are deducted. Importantly, these take effect in 2026 (the change to the SALT deduction takes effect in 2025). Because they are both calculated on the same schedule of the tax return, and the total is compared with the standard deduction, there is significant interplay between them in a holistic tax plan that optimizes for 2025 and future years.

Overview of Charitable Donations

There are actually several dimensions to the rules for deducting charitable donations. Over 90% of the clients I work with simply include the value of cash or donated goods as an itemized deduction. It is possible that your deductions can be limited if the value of your donations exceed a percentage of your AGI, but this is generally immaterial to physicians with mid six-figure incomes. Also, when you reach the age of 70.5, a very favorable strategy called Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) become available. Lastly, some taxpayers with significant taxable brokerage accounts take advantage of donor-advised funds as a tool for deducting charitable donations and eliminating capital gains taxes.

If these strategies appeal to you, I encourage you to discuss them with your tax advisor or financial planner (also feel free to message me or comment below if you would like for me to dedicate a future blog post to one or more of them). For now, I will focus on simple donations of cash or material property. To deduct the donations, they generally must go to a US-based tax-exempt organization (extra credit if you can name the three countries that have a treaty with the US allowing donations to qualify in limited circumstances). You also can’t receive anything in return, such as a membership or a raffle ticket. If you purchase an item for more than fair market value (such as at an auction), you can’t deduct the whole purchase, but you may be able to deduct the amount that exceeds fair market value. Donations to individuals do not count, either (they are considered gifts, the same as if they were made to a friend or relative).

When you donate cash, the amount of the deduction is very easy to value. If the donation consists of property, the rules are more complex. If you are donating used items to Goodwill, you estimate the value of the items at the time of donation. This is a good-faith estimate on your part, but there are guides available that can help you. If the property has increased in value since purchase (which describes real estate and investments), there are special rules that determine if you deduct the basis or the fair market value; that is a subject beyond the scope of this article.

Change #1 with the OBBBA - The Half-Percent Haircut

Starting in 2026, if you itemize your deductions, only amounts of donations that exceed 0.5% of your AGI are deductible. This would be $2,500 for taxpayers with an AGI of $500,000. For some taxpayers who make large donations every year (in keeping with their own values system), this likely won’t change strategy very much.

However, for taxpayers who donate more modestly, this may influence the timing of their donations, possibly leading to more bunching in 2025. For instance, if a couple earns over $500,000 per year, itemizes their deductions, and donates approximately $1,000 per year, they will not receive any credit for their donation in 2026 and future years. However, they would be able to deduct the entire amount in 2025, before this new rule takes effect. In this situation, it may make sense to clean out the closet before December 31st of this year. This is something I’ve wrestled with personally as my friends keep nagging me to get rid of my unicorn onesie and rhinestone jeans from the 1990’s. Fortunately, I’ll probably take the standard deduction, thereby sparing me the torture of that decision.

Change #2 with the OBBBA - Cash Deduction for Non-Itemizers

Some of you may remember that for a couple years during the pandemic, you could deduct a small amount of donations, even if you didn’t itemize your deductions. If you miss having this deduction available, there is good news with the OBBBA. Single and Married Filing Separate (MFS) filers can deduct up to $1,000 per year, and Married taxpayers Filing jointly (MFJ) can deduct up to $2,000. While donations may consist of cash or property for itemizers, only cash donations can be deducted for non-itemizers. Still, compared to the status quo, this is a clear win for those taking the standard deduction.

The considerations in tax planning for this deduction are in some ways the opposite of the approach I might take for taxpayers who itemize. While taxpayers who itemize may want to bunch more donations in 2025, taxpayers who take the standard deduction may benefit more from deferring their donations to the inception of the new $1,000/$2,000 deduction in 2026.

Putting It All Together

First of all, donating to charity is purely voluntary and optional. It can lower your taxes, but because the deduction is less than the donation itself, it is not a wealth-building strategy. I don’t encourage clients to donate purely to lower their taxes, nor do I judge those who decide against making donations. I bring this up as a planning strategy not so clients change their habits, but so I can help them financially optimize their current behavior.

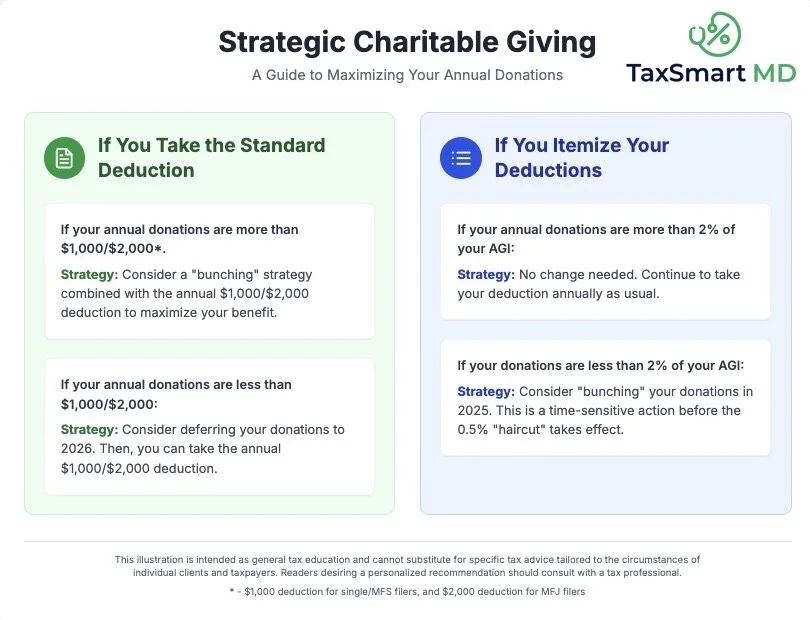

If you are already charitably inclined, the first step in determining the optimal strategy is figuring out whether you will take the standard deduction or itemize your deductions. As mentioned previously, the new SALT deduction changes this for most taxpayers, and your financial planner or tax advisor can help you answer this question, if you are uncertain.

If you see yourself itemizing in 2025 and future years, it makes sense to assess whether it is worth bunching donations in 2025 to avoid the Half-Percent Haircut later on. If you are someone who donates modestly, but with intentionality, this approach may best fit your situation. If you are someone who intentionally donates a significant percentage (2% or more) of your income to charity every year, it may be difficult or impractical to bunch donations this way. If so, the Haircut isn’t worth losing any sleep over.

On the other hand, if you take the standard deduction (because you don’t have much mortgage interest, or you don’t have a significant deduction for state/local taxes), consider how to make the most of the $1,000/$2,000 deduction for non-itemizers. If you have modest cash donations, consider pushing them to 2026. If you donate generously, consider whether it is worth doing a traditional bunching strategy so you can deduct a high percentage of donations one year (in which you itemize) and then take the standard deduction + $1,000/$2,000 in cash donations in other years.

There are other reasons you may want to target a larger deduction for charitable contributions in one year instead of another. For example, this comes into play with optimizing the QBI deduction.

I’ve included a simplified infographic that illustrates the framework described above.